Our Distinguished Guests: Exploring the First 30 Years of Athenaeum Hall

This summer the St. Johnsbury Athenaeum will host, for the 17th year, our series called Readings in the Gallery. These readings by noted poets and writers will take place this year, due to work in the art gallery, in the second floor space known officially as Athenaeum Hall. This series, as well as the First Wednesday lectures, the Osher Life Long Learning Series, and the many other readings and performances held throughout the years, are a continuation of the long tradition of free public events held here since Athenaeum Hall opened in 1871.

This exhibit highlights some of the distinguished speakers and visitors who graced this building, in the earliest years of its operation. It does, as well, situate the Athenaeum within the history of public lectures held throughout St. Johnsbury since the early 19th Century, and within the tradition of public education in the lyceum and Chautauqua movements.

St. Johnsbury Lecture Halls

St. Johnsbury had a vibrant lecture and public debate tradition before the Athenaeum was added as an additional venue for such gatherings. In The Town of St. Johnsbury -- A Review of One Hundred Twenty-Five Years to the Anniversary Pageant of 1912, Edward Fairbanks lists over a dozen different halls in existence between the opening of the new Town Hall in 1856 and the opening of the YMCA building in 1885. Of particular note for their capacity were: the Music Hall which seated over 1100, the New Academy Hall with a capacity of 1250, and Howe’s Opera House with a capacity of 1500.

Athenaeum Hall was one of the smaller halls but has the distinction of being intended to be used for educative purposes only, without expense to the public (Fairbanks, p. 341.).

The largest halls were filled by ticket holders who bid for the best seats, ticket sales providing the revenue to bring in the most renowned speakers available. The practice of paying speakers to travel to an area is very much in the style of the lyceum movement. Large, enthusiastic crowds and popular speakers made a modern functional hall a necessity. Lack of such, in pre-1856 St. Johnsbury, is noted by Fairbanks in this unattributed quote, likely an editorial comment from the Caledonian Record:

September 8 1855 It is like enduring the tortures of the Black Hole to stay in the low unventilated dungeon of our Town Hall at the Center Village the air nauseated with smoke and exhalations from 700 pairs of lungs so that even the lamps go out for want of oxygen to keep them burning More than any necessity for County Buildings is our need of a new wholesome capacious Town Hall

The New Town Hall answered the call for such a facility beginning in 1856. Many noted speakers and dignitaries, two presidents even, were feted at Athenaeum Hall when it became available in 1871.

Lyceum and Chautauqua Movements in St. Johnsbury and New England

The great capacity of the largest halls in St. Johnsbury indicates a ravenous appetite for the public lectures, debates, and entertainment in the tradition of the lyceum movement, a 19th-century American system of popular instruction of adults by lectures, concerts, and other methods. The Lyceum movement was popular through out New England.

This was a public education movement that began in the 1820s and is credited with promoting the establishment of public schools, libraries, and museums in the United States. The idea was conceived by Yale-educated teacher and lecturer Josiah Holbrook (1788-1854), who in 1826 set up the first "American Lyceum" in Millbury, Massachusetts. He named the program for the place-a grove near the temple of Apollo Lyceus-where the ancient Greek philosopher Aristotle (384-322 b.c.) taught his students. The lyceums, which were programs of regularly occurring lectures, proved to be the right idea at the right time: They got under way just after the completion of the Erie Canal (1825), which permitted the settlement of the nation's interior, just as the notion that universal, free education was imperative to the preservation of American democracy took hold. The movement spread quickly. At first the lectures were home-grown affairs, featuring local speakers. But as the movement grew, lyceum bureaus were organized, which sent paid lecturers to speak to audiences around the country. By 1834 there were approximately 3,000 in the Northeast and Midwest. In their heyday the lyceums contributed to the broadening of the school curricula and the development of local museums and libraries. After the Civil War (1861-65), the educational role of the lyceum movement was taken over by the Protestant-led chautauquas.

(http://www.answers.com/topic/what-was-the-lyceum-movement)

Social changes occurring in post-war America included the emerging democratization of education. During the 1870s, the Methodist Episcopal Church held summer training sessions for its Sunday school teachers and other church workers. At the annual assembly of 1874, held at Lake Chautauqua in western New York State, it was decided to broaden the curriculum's frankly religious nature to include the arts, humanities and sciences. As the years passed, more emphasis was placed on singing groups, oompah bands, theatrical presentations and magic lantern shows. The advent of the railroads and their cheap fares had made it possible for working-class families to attend the sessions. The Chautauqua gatherings became a blend of a county fair and revival meeting.

By the turn of the century, many communities had formed their own “chautauquas,” unrelated to the New York institution, that paid lecturers and performers to participate in their local events. Following World War I, the availability of automobiles, radio programming and motion pictures eroded the Chautauqua Movement's appeal. Independent local activities died out, but the national organization has continued on a reduced scale to the present day. (http://www.u-s-history.com/pages/h1202.html)

The St. Johnsbury Lecture Tradition

In The Town of St. Johnsbury Fairbanks describes the activities of The St Johnsbury Literary Institute beginning in 1850. (It) was composed of citizens with a principal design of providing courses of lectures for public entertainment. In this the Institute was very successful and for several years courses of a high order of merit were maintained. There were lectures on history, literature, travel, invention, applied science, and kindred topics that filled the meeting house with interested listeners.

In 1851 the course was fourteen lectures, in 1854 there was a course of eleven lectures total expense $312.36. Some years later the work of this Institute was taken up by the YMCA whose annual Lecture Course, maintained for forty years, became justly famous.

The Lecture Course inaugurated by the YMCA in 1858 and re-established in 1867 brought in an annual series of lectures and concerts of exceptional merit and distinction. It has been repeatedly remarked by non-residents that no other town of its size in New England has had so many distinguished speakers and musicians as this little village among the hills. Thro the generous patronage of citizens it was possible to secure talent of the first order. This was true during the years when churches and Town Hall were the only places of assembly. After the acquisition by the Association of Music Hall in 1884 there was a rising tide in the popular interest, every seat in the Hall being taken. Preliminary sales of course tickets were held at which premiums were paid for the choice of seats.

The following partial list of speakers in St. Johnsbury indicates the acclaim of the YMCA lecture series: Henry Ward Beecher, Robert Collyer, John B Gough, Edward Everett Hale, Lyman Abbott, Booker Washington, Henry M Stanley, George Kennan, Robt E Peary, Gen Lew Wallace, Gen Jos Hawley, Russell H. Conwell, Gen Joshua Chamberlin, Gen Gordon of GA., Horace Greeley, Frederick Douglass, Jacob Riis, Bayard Taylor, Thomas Nast.

Fairbanks also notes the public events of the St. Johnsbury Woman’s Club. Among public entertainments provided by the Woman's Club, not to speak of many musical ones, have been addresses or readings by Mrs. General Custer, Julia CR Dorr, Sallie Joy White, Kate Gannett Woods, Alice Freeman Palmer, Mabel Loomis Todd, Katherine Lee Bates, Isobel Strong, Frances Dyer, with now and then an interesting man on the rostrum for variety.

The Opening of Athenaeum Hall

The public opening of the Athenaeum was preceded by three addresses on successive evenings delivered in the Hall which was filled to its utmost capacity. The first by Andrew E. Rankin Esq was on the educational importance of the library as a school of learning and culture. The second by Lewis O Brastow, then pastor of the South Church, on the dignity and worth of refined literature. The third by Edward T Fairbanks was a colloquy in which Bion Mago and Quelph talking together while inspecting the alcoves and dipping into the pages of the books gave an outline description of the treasures here stored for the use of the people.

The Athenaeum Hall was intended to be auxiliary to the educative use of the library. Series of popular lectures of special interest were provided. Dr John Lord gave ten which are now included in his Beacon Lights of History. Prof John Fiske gave a course on American History. Prof WD Gunning a series on the Life History of our Planet. Lectures and concerts have been given under auspices of our home institutions The Hall was designed to serve the public benefit only and no entertainment for personal profit has ever been admitted.

Among the most distinguished guests in Athenaeum Hall was the 23rd President of the United States Benjamin Harrison. He spoke from the now-gone front balcony on August 26, 1891.

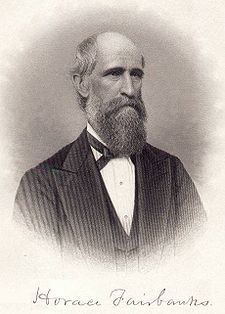

While not all of the individuals named in this exhibit delivered talks here at the Athenaeum, may of the most well known were in all likelihood feted here with a reception. In the late 19th century the Fairbanks family and its namesake company was at the peak of its power and influence. Erastus Fairbanks was, among many other roles, Governor of Vermont in 1852-1853, and again in 1860-1861, and his son, Horace, founder of the St. Johnsbury Athenaeum, was Governor in 1876-1877.

The St. Johnsbury Caledonian has this to say regarding the Athenaeum in its December 1, 1871 issue:

The present week has been a proud one for St. Johnsbury. The long-cherished plan of one of our honored citizens, of erecting a Free Public Library and presenting it to his native town, has this week been consummated…. As announced in the last Caledonian, a short course of lectures was commences at Athenaeum Hall, on Thursday evening Nov. 23rd, preliminary to the opening of the library to the public. At the hour appointed the hall was filled solid full with an audience of about six hundred our four citizens, attracted together with the treble thought of hearing the lecture, seeing the new hall, and doing honor to the giver. The audience was surprised at the outset by a flute trio, after which Mr. Horace Fairbanks welcomed those assembled in a few choice words, expressing his gratitude at their attendance, and introduced the lecturer for the evening, Mr. A. E. Rankin.

Thus began the tradition of free public lectures in Athenaeum Hall that continues to this day.